"Children behave, That's what they say when we're together, And watch how you play, They don't understand, And so we're, "Running just as fast as we can, Holdin' onto one another's hand, Tryin' to get away into the night, And then you put your arms around me, And we tumble to the ground, And then you say, "I think we're alone now, There doesn't seem to be anyone around. I think we're alone now, The beating of our hearts is the only sound."

In return I gave her a very crudely-made mix-tape that I think included music ranging from the Stones' Sweet Virginia to Al Green romantic classics.

Which of us was violating copyright? Which of us was committing plagiarism?

Stick with me here for just a bit, but think about that question while you do. And add in this... what if instead of a letter she had sent me a You Tube playlist. What if I had shared digital music files with her - perhaps (gasp!) across a computer network at an American university.

Let's put it another way. What if the United States government decided it would open mail being sent to US citizens. No, not all mail. Just all the mail sent to the US from foreign nations. And what if - well, they were just scanning it for keywords and patterns, you know, not really "reading" that letter from your girlfriend vacationing in Algiers - just "scanning" it in order to improve "national security" - no warrants seen as necessary.

Yeah - you'd be outraged. Of course. (The US government has never admitted to doing anything like that, though during World War II they did ask the Brits to do it for them with any mail passing through any British territory.)

But you are less sure - clearly you are less sure - if the same thing is done with emails or mobile phones. You probably (if you read my kind of opinions) think the government is wrong to do that but you're not upset in quite the same way. You are not (perhaps, for example) bashing down Hillary Clinton's Senate office door because she thinks it is ok for the US government to do that.

What does this have to do with education?

Here's a side story. In university classroom after university classroom I see many students carrying print-outs of texts provided to them digitally. Articles, book chapters, powerpoints - all of which have been provided by faculty in digital form or which have been accessed from digital library files - are converted into "ink on paper" because the student "is more comfortable" with that format - they find it easier to (choose one or more) hold, carry, read, highlight, refer to, file. And all of them do that without getting special permission. Not one student who does that needs to bring personal psychological evaluation records to a "disability office" and receive special permission. But - yes, here we go - any student who wants to do the reverse - that is to convert paper text into electronic form and use it in the classroom, needs to give up all of their privacy rights, and often a large chunk of their dignity, in order to be afforded the same "media switching" privilege.

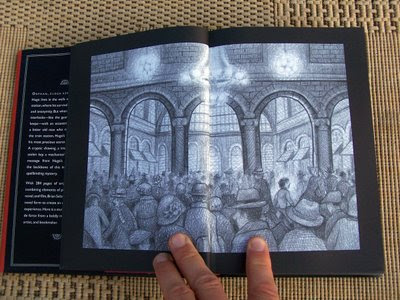

Two things brought this into new focus for me in the past week. First, I read The Invention of Hugo Cabret - the brilliant winner of the Caldecott Medal by Brian Selznick. More on this in a moment.

Second, The Economist began a new debate: "Security in the modern age cannot be established without some erosion of personal privacy." (appearing there again as "PostColonialTech"). Neil Livingstone, in arguing this proposition (and the inherent goodness of it) includes this quote in his mid-debate rebuttal, "This includes the use of surveillance cameras, access to major databases, telephone and email intercepts, and various methodologies for authenticating identity." Notice - he does not suggest the widespread opening of mail, nor the use of general listening devices which might - for example - allow the military to (warrantlessly) survey his living room conversations with his wife, though, in truth, terrorist intentions can - and clearly have - been passed through these "more antique" communications systems.

In other words, Mr. Livingstone is not interested, really, in either privacy or security. What he is worried about is a technological communications grid that he does not (truly) understand.

Because, let's face it. If I post a blog I have no more expectation of privacy than if I write a letter to the editor or publish a newspaper. But if I send an email or call someone from a non-public location, my expectation should be that it is every bit as private as the "snail mail" letter I send. These are the same forms of communication no matter how different the format is. But neither Mr. Livingstone (who NBC declares "an expert"!) nor schools nor employers nor the governments of the US or UK understand this.

Which is why this is an educational issue and a disability rights issue.

Let's go back to the top and Tommy James and the Shondells - a group so fundamentally unhip that Hubert Humphrey wrote the liner notes for one their albums (just had to mention that with real apologies to "Katie"). The letter from the girlfriend was inaccessible text, but was, in the rationalised assumptions of modernist educational and political philosophies, a perfectly legitimate method of quoting (as long as she indicated source and copyright, of course). My mix-tape cassette response was far more accessible (in terms of content delivery if not emotionally), but those same rationalised assumptions struggle with whether I am allowed to do what I did. Shift it to the far more accessible You Tube or to a file sharing system and everyone over 35-years-of-age now calls it "illegal file sharing."

In other words - the media which work for Mr. Livingstone or for your typical teacher or Minister of Education, well, that's protected, sacred, good, safe, etc. The media which work for me, well those are in an opposite category.

Post-Medium-Specific

Brian Selznick's The Invention of Hugo Cabret, named the most distinguished American picture book for children this [2007] year, (yes, back to that) emphasizes this. Mr. Selznick has made a film - about that there is no doubt - but the film is presented as a bound book. Instead of sitting in the theatre, though, or in front of your TV, you turn the pages, rapidly in fact, to take in the tale at the speed of film. Which forces one set of global questions: What does "book" mean? What does "reading" mean? How is "reading" different than "listening," or, specifically, "watching"?

It also raises some personal questions. Since the world of post-graduate education is so caught up in format rather than content, since my university has far more rules about how to bind a thesis than how to make it accessible, could I create a thesis that was a series of drawing as long as I bound it properly for dust-collecting storage in the basement of the library?

I thought of that because in the same week as I read The Invention of Hugo Cabret a professor told me that she considered quotes without cited page numbers to be "plagiarism." When I noted that those of us who utilise alternative formats do not always get accurate page numbering she said, "I never thought of that," but she didn't back down. In education format rules still consistently trump content and communication. And this, as The Economist Debate reveals, is true in government laws too.

But for most of us - we are moving into a "post-medium-specific" world. Brian Selznick puts a film on paper. Amazon puts books on Kindle. Audiobooks make books into podcasts. Television shows appear on your computer. Japanese readers read novels on their mobiles. We have reached a point where we can pick the content and the medium, making it our own in crucial ways.

And that benefits - in massive ways - the huge percentage of the world that has always struggled with "classic" content delivery.

But let me say this - it has both always been this way (at least in one direction). I've seen many teachers of English who ask their students to read Shakespeare (clearly separating content from medium). And Homer, after all, is just a written version of something always intended to be heard. It is like those who print out online PDF documents, or those who read press conference transcripts, we grab for the medium which serves us best.

This does not mean that authorial intent goes out the window. No one is suggesting we eliminate any formats, or that we shouldn't embrace the diverse ways of knowledge available through different formats - a brief digression to "read" from the blog of London design student Gregory Stevenson on Hugo Cabret: "An interesting upside of the imaginative constraints that come with reading a picture book is that it gives the author more control over what the reader sees in their mind’s eye. If a novelist just uses words, the ‘visual story’ created in the reader’s mind will be particular to them – and, for example, a character is likely to appear differently to each of them. Where there is an image of that character, there is no room for interpretation, and no need for conjuring. So, in Hugo Cabret, when we read the text passages what we imagine is likely to have visual continuity from Selznick’s pencil drawings. It’s often said that featuring a protagonist on the cover of a novel is a no-no, because of this very fact – it stops them from imagining their own. But in some instances, maybe this would be useful to an author. An imagined example: some small detail of a character’s appearance is important to the plot. By showing it to us, it becomes fixed in our memory – and in a different way from how we see it in our minds as we race over the text. In Hugo Cabret, another function of the image sequences is in moving the action along at a cracking pace – at least halving the reading time of a book describing the same action using text. This probably explains why I didn’t tend to luxuriate in the pictures, studying the details, as I’d imagined I would. It would have been like freeze-framing a film in the middle of an action scene to admire the colours and composition. It was only when I’d finished that I flicked back to enjoy the pictures as pictures."

Now, think of the ways altering the medium can alter perception and processing. Go back up in this post... if you don't know Tommy James and the Shondells or their song I Think We're Alone Now this medium offers you instant access - right-click on the link and say "open in new tab" and you have it - a "live citation" - the kind that, for my professor friend, makes APA Style and its page numbering requirements not only a quaint anachronism, but a fourth rate method of conveying information.

Or take either the new illustrated version of Seamus Heaney's translation of Beowulf or the 2007 film. Both alter format to deliver content in ways far more accessible than those "old" versions.

The trick is that now, to a significant extent, we can put the power to switch media in the hands of each student, in each human. We can celebrate content and content delivery over the orthodoxy of format. Yes, that is challenging. It pulls the power away from teachers, instructors, and traditional publishers. It requires new thoughts on copyright, on ownership of intellectual property. It surely involves new risks - to everything from "national security" to the transmission of facts. But those are risks we must take.

We must take these risks because the new post-medium-specific world is too important. It is vital to the liberation of so many from the tyranny of the "favoured format." It is essential to expansion of education and human communication. It is necessary, in these days when miscommunication is both so easy and so dangerous, for the likely survival of humanity.

I write mostly about students with "disabilities," but this goes far beyond that. We have too long frustrated human freedom and human learning with arbitrary and nonsensical allegiances to format. Use a number 2 pencil, or this type of pen. Make sure you double-space. Read this edition. Write in this "blue book." Make sure you use "APA" style (or MLA style, or whatever). Sit in that seat. Take this course at this hour. And all these rules have done is limit and exclude and separate and impoverish.

Even if our technology was not what it is we should know better - Brian Selznick needed nothing "21st Century" to put a film on paper - but our current technology wipes out all of our excuses. So let us stop the tyranny, and embrace media choice in a very real way.

- Ira Socol

Essential Blog Alert! - Over at jamessocol.com a three part series on web accessibility. Part one explains the issue, part two helps you analyze, part three helps you design, If you have any educational website this is vital information that you must read...

The Drool Room by Ira David Socol, a novel in stories that has - as at least one focus - life within "Special Education in America" - is now available from the River Foyle Press through lulu.com

The Drool Room by Ira David Socol, a novel in stories that has - as at least one focus - life within "Special Education in America" - is now available from the River Foyle Press through lulu.com

US $16.00 on Amazon

US $16.00 direct via lulu.com

Look Inside This Book