You like to spend time with your family. 5 (yes, definitely) 4 3 2 1 (No)

"They were poor because they were lazy, they were lazy because they were Catholic, they were Catholic because they were Irish, and no more needed to be said. This was the transatlantic consensus about Irish Catholics, and it was preached from the finest pulpits and most polite salons in London and uptown Manhattan." - Golway, Terry (2014-03-03). Machine Made: Tammany Hall and the Creation of Modern American Politics . Liveright.

I've been reading Machine Made: Tammany Hall and the Creation of Modern American Politics

But a critical part of what the book forces is a historic consideration of "Grit" - a consideration that dives way back - before the antisocial imaginings of Angela Duckworth's favorite author, Thomas Galton.

|

| New York City: Irish Hunger Memorial |

You'd prefer to listen to your friends' stories than do math exercises. 5 4 3 2 1

So that Irish "laziness" - a British and American description - has a history which is deep and complex, and not at all without benefit. Though Angela Duckworth may see herself as a gritty success and the Irish cop patrolling the area outside her Philadelphia office window as a failure without aspiration, others might see it differently.

"Within Irish literary modernism, originating with Wilde and further developed, especially by means of formal experiments in narration, by Joyce, Beckett and Flann O’Brien, lies an alternative version of modernity which gives to an historically complex concept of idleness the centrality that capitalism and nationalism give to work. Other writers, Yeats and Eimar O’Duffy among them, elaborated a role for the intellectual in the formation of the State, but this was consistently challenged by the notion that labour and work have an oblique and often sterilizing impact on creativity and emancipatory politics." Gregory Dobbins, Lazy Idle Schemers: Irish Modernism and the Cultural Politics of IdlenessIs a disbelief in that "Protestant Work Ethic" a moral failing? An academic failing? A national failing? Or is the commitment to 'working hard' simply for the sake of 'working hard' - as expressed in Angela Duckworth's "Grit Test" - not the only path to success in life?, Field Day Publications, 2010

A good meal with friends is a worthwhile way to spend an evening. 5 4 3 2 1

"This was a battle that Tammany’s Irish voters recognized as a variation on a conflict that, to a greater or lesser extent, drove them out of their native land. Ireland’s Catholic majority had long been engaged in cultural and political conflict with an Anglo-Saxon Protestant ruling class that viewed the island’s conquered masses as victims of moral failings and character flaws that encouraged vice, laziness, and dependence and rendered them unworthy of liberty." Golway (2014).

That "moral failing" - that eugenicist belief that disconnects between institutions and humans always suggests a failure of the humans - lies at the heart of Duckworth's beliefs, and the "Grit Narrative" as a whole.

"Probably the finding that most surprised me was that in the West Point data set, as well as other data sets, grit and talent either aren't related at all or are actually inversely related.Notice that the cab drivers Duckworth discusses are not shirking any responsibilities, but they are still failing in her description because they are not working regardless of need. "Calvinism does require a life of systematic and unemotional good works (interpreted here as hard work in business) and self-control, as a sign that one is of God's chosen "elect." Thus, ascetic dedication to one's perceived duties is "the means, not of purchasing salvation, but of getting rid of the fear of damnation."'

"That was surprising because rationally speaking, if you're good at things, one would think that you would invest more time in them. You're basically getting more return on your investment per hour than someone who's struggling. If every time you practice piano you improve a lot, wouldn't you be more likely to practice a lot?

"We've found that that's not necessarily true. It reminds me of a study done of taxi drivers in 1997.* When it's raining, everybody wants a taxi, and taxi drivers pick up a lot of fares. So if you're a taxi driver, the rational thing to do is to work more hours on a rainy day than on a sunny day because you're always busy so you're making more money per hour. But it turns out that on rainy days, taxi drivers work the fewest hours. They seem to have some figure in their head—"OK, every day I need to make $1,000"—and after they reach that goal, they go home. And on a rainy day, they get to that figure really quickly.

"It's a similar thing with grit and talent. In terms of academics, if you're just trying to get an A or an A−, just trying to make it to some threshold, and you're a really talented kid, you may do your homework in a few minutes, whereas other kids might take much longer. You get to a certain level of proficiency, and then you stop. So you actually work less hard.

"If, on the other hand, you are not just trying to reach a certain cut point but are trying to maximize your outcomes—you want to do as well as you possibly can—then there's no limit, ceiling, or threshold. Your goal is, "How can I get the most out of my day?" Then you're like the taxi driver who drives all day whether it's rainy or not." - Angela Duckworth, The Significance of Grit: A Conversation with Angela Lee Duckworth, ASCD Educational Leadership, September 2013 | Volume 71 | Number 1

In the fall of 2014 I was in a cab in New York City and the driver and I were discussing a neighborhood we had both been young in - I in my 20s he as a tween - and how we'd survived the crime-ridden time, and then, this was the opening day of the United Nations General Assembly amidst massive climate protests, I asked what he would be doing after he took me and my colleagues from Brooklyn to Queens. "I'm going home to play with my kids," he told me. "If I drive and someone gets in and wants to go to Manhattan I'll have to go, and the traffic will be a disaster. That's just not worth the money."

A man with 'no Grit,' I laughingly thought, tipping him very well. But a man I respect all the more.

You make time to play often during each week. 5 4 3 2 1

Like the Irish of the mid-19th Century - or perhaps the 20th Century - the mostly African and Caribbean taxi drivers of contemporary New York are neither "white," nor "Anglo," nor "Protestant" in fact nor disposition, and Angela Duckworth and "Grit" advocates, like the "reformers" and moralists of the 1840s-1850s, are troubled by a different set of moral imperatives. If the Irish chose "limited opportunities," municipal jobs which were secure and held guaranteed pensions over riskier entrepreneurship with potentially larger payoffs, this was disturbing to the power elite. If African and Caribbean cab drivers choose to go home to their families rather than amassing additional wealth, this disturbs Duckworth. If students choose to "get by" in school rather than chasing the "As" and pursuing Duckworth's Ivy League path to success, this disturbs the Grit advocates in American schools.

|

| "No Irish need apply," was a common employment advertisement tag line in the 19th Century It is a peculiar thing that we limit opportunity for those we then criticize as lacking motivation. |

You enjoy sitting outside doing nothing. 5 4 3 2 1

Back in the last century - long ago I guess - a classical literature professor, one of the very best, told us that the most important dividing line in Europe was the old Eastern/Southern Boundary of the Holy Roman Empire. "Americans know nothing because they ignore the historic realities," he said (or something like that) as he explained why Czechoslovakia had split, why Yugoslavia had shattered, why even Italy was hopelessly divided, north and south.(2) The divide, created centuries ago, remains an essential reality of culture, an essential reality of understanding. Those perceiving themselves as having "been included" see themselves as "right." They see those on the other side as "lazy," or to use our current terminology, "lacking Grit."

|

| Czech Republic, in - Slovakia, out. Slovenia and Croatia, in - Serbia and Bosnia, out. Northern Italy, in - Southern Italy, out. The Holy Roman Empire created a cultural divide lasting to this day, as the England/Ireland divide remains. |

“Their means of resistance —conspiracy, pretense, foot-dragging, and obfuscation —were the only ones ordinarily available to them, ‘weapons of the weak,’ like those employed by defeated and colonized peoples everywhere,” wrote historian Robert James Scally in his masterful re-creation of Irish townland life." Golway (2014)

You are fascinated by new things you discover. 5 4 3 2 1

|

| How many American history textbooks celebrate the work of political cartoonist Thomas Nast? I don't need to take "someone out of their era" to know a vicious racist, anti-Catholic nativist, and to wonder why his work is used, without caveat, in our schools... (Irish were always portrayed as apes in his work, Catholic Cardinals sometimes as crocodiles) |

Taking Duckworth's test I got a "Grit Score" of 1.25, or "grittier than 1% of the population." Ah well, perhaps I have other attributes, attributes worth valuing. It's possible, right? As it is possible that our "ungritty" kids might have other attributes, or might need other things. After all, as I asked at EduCon, "if I managed to get thrown out of your class every day, wasn't I exhibiting grit by Duckworth's measures?" I mean, if it isn't just compliance, as I've suggested more than once, than that kind of commitment to a task demonstrates grit? right?

You enjoy books and stories that have little to do with your daily work. 5 4 3 2 1

"Protestant areas of the island [of Ireland] because “we are a painstaking, industrious, laborious people who desire to work and pay our just debts, and the blessing of the Almighty is upon our labour. If the people of the South had been equally industrious with those of the North, they would not have so much misery upon them.” Golway (2014).

If the 'Grit Narrative' isn't about compliance it is false. If it is about compliance, if all Angela Duckworth wants is for poor kids to behave like her, it is racist and classist and Calvinist (in a political, not a religious, way).

But if our narrative is a question of a lack of abundance, it suggests different tools for our use within our schools. If the British government had stepped in during the 1840s Potato Blight and stopped the massive exports of food from Ireland - stopped the exports so that the Irish could eat rather than letting 1.5 million people starve to death - then the Irish communal memory might be very different, and the aspirations of those who left Ireland and crossed the oceans might have been different. If those nations outside the boundaries of the Holy Roman Empire had not been treated like colonies to be pillaged, the history of the Balkans in Europe might look different. Had African-Americans actually been liberated - liberated from enforced poverty and powerlessness - at the end of the Civil War, the African-American communal memory might be different, and hopes might look different in many communities.

If the poor in America actually saw a path to possibility, then community vision today might be different.

You are willing to shift from one task to another based on interest and value. 5 4 3 2 1

So the only role schools might have today is to offer abundance, not training in grit. We can offer what people have not had, offer 'wealth' of resources, and offer possibilities. And at the same time understand that differing cultures value differing things, and the 'Protestant Work Ethic' is just one path, and not the only path, not necessarily the best path, not necessarily the one moral path.

We offer kids the abundance of choices and that offers an abundance of possibility.

- Ira Socol

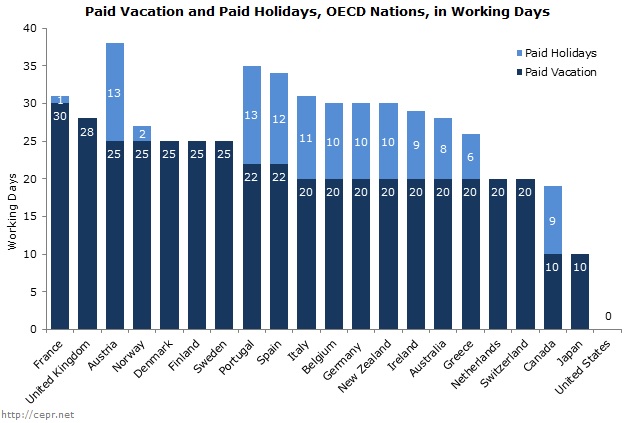

(1) If you've ever been to Europe (besides the U.K., the Scandinavian countries, protestant Germany, and Switzerland), or if you’ve been to Mexico, or Central or South America (or most of the rest of the world), you've probably noticed that these cultures have an entirely different orientation to work and leisure from that of most U.S. people. Residents of these other countries are usually baffled by the frantic "workaholism" typical of the U.S. (and parts of Northern Europe). These people can put in grueling hours, as U.S. citizens commonly do. Unlike U.S. residents, though, if they work tremendously hard, it's because they need to do so -- the job requires it, they need the money, or some such thing. They make a conscious decision in favor of it.

Most U.S. people, on the other hand, seem psychologically impelled to work much too hard for no obvious reason. Many of us actually feel guilty if we aren't working much too hard. And we tend to think very highly of people who hate what they do; that is irrationally seen as somehow more virtuous than having a job one loves!

This workaholic attitude is often treated (by people in the U.S.) as just common sense, just part of human nature. It's not. It's a distinct phenomenon, only a few centuries old (that is, very, very recent in terms of human history), localized to a few areas of the globe, and with specific causes in those areas.

(2) Years later, in this century, I was faced with Robert Putnam's work on the divide in Italian democracy in a research methods class. I earned the undying enmity of a brittle MSU prof by challenging this Harvard publication. "He never considered history before the 19th century," I argued, "he never looked at the inside/outside of the Holy Roman Empire." How could I doubt the Ivy League author of the famous Bowling Alone? I could for the same reason I doubt Angela Duckworth's work. I find that both ignore the facts of history and culture.