How might a five-year-old describe the way water pours?

And what about a kid telling a story?

When kids come to school at five (if kids should come to school at five in the first place) they have certain fascinations - hearing and telling stories, understanding signs, the physics which make their world work, hot and cold, animal behaviour. And great teachers do embrace much of this, but our school curriculum never does.

Instead of running with this natural learning curve, instead of meeting our students where they are, we focus all of our attention through the age of eight on a certain set of formalized learning systems which disinterest most kids, and are essentially impossible for many. We spend all of our time on complex symbolic codes (the alphabet, the numeral system) and on the operation of those code systems (phonics, spelling, arithmetic).

And, within three years, we have taken kids thrilled to start school and turned them into kids who'd rather be anywhere else.

Last night on Twitter I had a conversation with college professor Michael Walters - @rugcernie. At one point he was troubled when I said that we had to, "meet students where they are." "by making the practice "meeting them where they are," you may lower standards. Balance must be struck," he said.

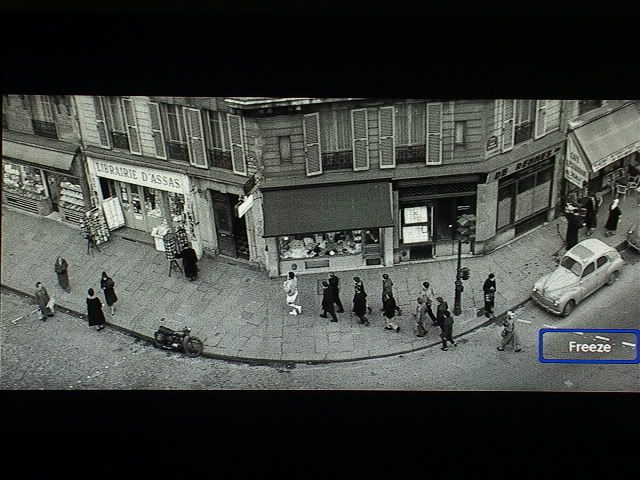

When he said that I thought of the classic scene from Francois Truffaut's film Les Quatre Cent Coups (400 Blows). A teacher takes the boys out on a physical training run through Paris. Two by two, three by three, they vanish from behind him, running off into shops and alleys. By the time the scene ends the teacher is no longer being followed by 40 students, but by one. "You can't bring anyone anywhere if you start where they are not," I suggested.

Imagine a tour leader waiting on a corner ten blocks away from where the group going on the tour has gathered. This is what most education looks like. We're frustrated because students are not following along, but the students can not follow because we are beginning where they are not.

And thus, the one-third who succeed are those who either somehow luck out into being at our starting point or who, essentially, don't need us in the first place, and the other two-thirds muddle along in failure, year after year after year.

Green percentage are students proficient in reading at grade four, according to US National Assessment of Educational Progress through 2009

And it never gets any better. The students aren't following at the start, and so they can never catch up.

Green percentage are students proficient in reading at grade eight according to US National Assessment of Educational Progress through 2009

This creates not just overall failure, but creates disability as well. Because we do not want to admit that our system is flawed, we label our children as flawed. We don't look at the charts above and see a system which is ignoring children, rather, we describe those falling in the orange zones as "retarded," whatever polite words we choose. Thus, it is the kid's fault, and we can go on and on as before.

But what if school began differently?

I'm not promoting Montessori specifically, but they surely understand the idea

So do many hands-on museums (here, the New York Hall of Science)

What if school began with where kids actually are? With the bounce of a ball, the spin of a playground ride, the stories of their mornings, their obsessions with cars, planes, boats, or dolls? What if we allowed kids to create their own paths from their own starting points? What if letters, numbers, reading, counting, multiplying were only introduced as it appeared as a problem-solving solution for the student's interest?

Then that learning wouldn't be the worthless chores they now appear to most kids, but rather, as a route to where the student wants to go: Wouldn't you like to read this story about Nascar, Arsenal, the Titanic, knights, off-road-vehicles? Let's start with text-to-speech, so you can listen and watch...

And if the student wants to go there, the learning is motivated. And motivated learning is effective learning.

In 1865 the New York State Board of Regents cranked out the first standardized test of general education. About one-third of students did well. Today, 145 years later, our school curriculum system is the same, and so are our results.

So, do we keep insisting that our students change? That our teachers change? Or do we change our system?

- Ira Socol

3 comments:

"And if the student wants to go there, the learning is motivated. And motivated learning is effective learning."

Does it matter what students are learning? Or only that they are learning? Does it matter where they go, or only that they are going somewhere?

It was fun to read your article with my five year old. She is blessed to attend a school that does meet the students where they are. They used a Reggio approach to learning, and as an educator, it was hard to trust the system as it differed from what I knew in school, but I'm seeing the benefits and joy each day now as her soul wants to explore more and more. The challenge for me is how do I make this happen at the middle level. We are working on it though.

As a teacher working with high school students who have significant intellectual difficulties this article really struck me. The biggest challenges I face are trying to meet the academic needs of my students while convincing colleagues and parents alike that 'non-credit' classes are just as valuable as those 'credit' courses which move the student toward a traditional diploma. Putting a grade 9 student into a mainstream grade 9 English course in order to work toward credit when the student is struggling with reading and comprehending grade 1 level text and audio information is merely a study in frustration for everyone involved. But put that student into an individualized literacy program that meets them at their level, and you get a rewarding experience for everyone, where the student is able to meet expectations and make progress in their literacy skills.

If you are teaching things that are ahead of what the student is ready to learn you might as well be teaching neurobiology to a newborn.

Post a Comment