Heros for our children

I can’t claim to remember the specifics. Yes, I’m old enough to have been in school, but there were a lot of other things going on during those school days.

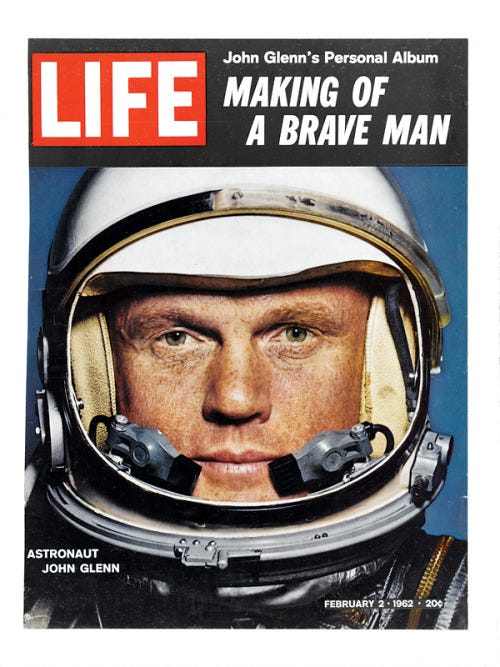

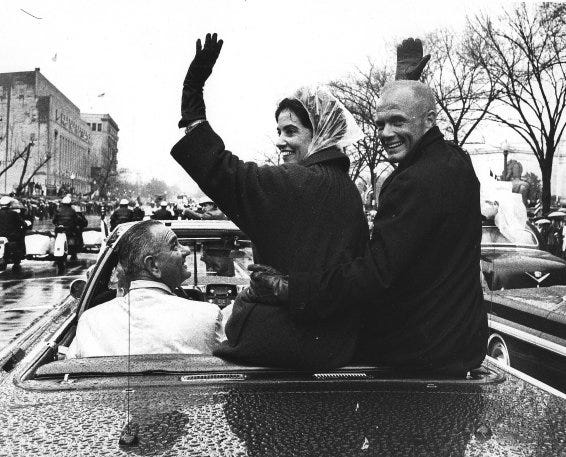

Still, by all reports I was obsessed with astronauts and space. I’d spend hours with the pictures in Life magazine. I had coloring books and sticker books and a paperback version of You Will Go to the Moon. I was a major Alan Shepard fan, but John Glenn was mighty cool too.

But if I can’t quite remember I still know the scene exactly. My gigantic elementary school had a thousand-theater-seat auditorium, but that wasn’t nearly big enough for the whole school. Across the main hall from that giant room was a smaller, more ‘spartan’ space — maybe 250 seats without cushions, but still an auditorium — though we called it the “General Purpose Room.” It’s is that room that I have in my vision.

An enormous — black and white of course — television on a huge rolling stand has been wheeled to the center of the stage, and tuned to Channel 2, WCBS-TV, and Walter Cronkite. And we would watch, waiting for the moment when we could shout the countdown along with — was it Chris Kraft? — as soon as we got to “T minus 10.”

Once upon a time we were surrounded by heros. Listen, I could add the postmodern spin here — John Glenn was the third human to orbit the earth and the fifth to be launched into space, not exactly Columbus — but my point is the opposite. So, once upon a time we were surrounded by heros.

I came to world awareness surrounded by John Fitzgerald Kennedy, The American Astronauts, Pope John XXIII, Martin Luther King, John Lewis, Robert Kennedy, Walter Reuther, Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, Sandy Koufax… a pantheon laid on top of the heroic narrative of our fathers and grandfathers who had crushed Nazism, defeated Imperial Japan, tamed the nucleus of the atom, and beaten the Great Depression.

Heros matter.

About five years ago I stood outside the White House fence in Washington DC. On my right was an African-American mother and perhaps 10-year-old son. And I realized, in that moment, the power in the face that that little boy knew that the President inside that mansion looked like him. Just as John Kennedy’s election had meant so much to my father — and thus, by extension, to me. I had hoped this January might bring a similar effect for our girls, but…

Heros matter

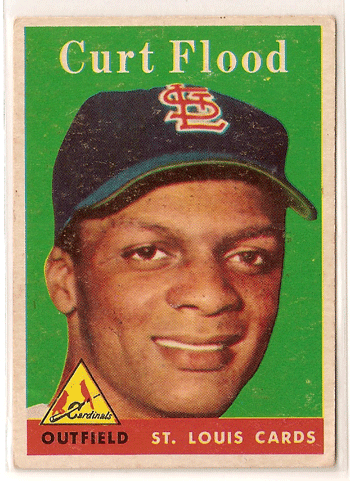

And we don’t offer our children heroes any more. We offer celebrities, but that is different. There are some really nice sports figures these days, but where is the heroism of Curt Flood — tossing away his career for a point about race and labor. Or even a Sandy Koufax — refusing to pitch a World Series game because of his religion. I sort of hoped that LeBron James would walk the small cities of Ohio campaigning for what he believed in, risking his home state popularity for a cause… but that didn’t happen

.

There are some good politicians, but where is the John Kennedy going into Protestant Texas to talk about religion? Or Attorney General Robert Kennedy going into fully segregated Georgia to demand and integrated nation? Where is even the Nelson Rockefeller actually getting things hurled in his face as he tried to stop his political party’s roll to extremism? Where are the political leaders marching at the head of anti-racism protests, daring the police to hit them first?

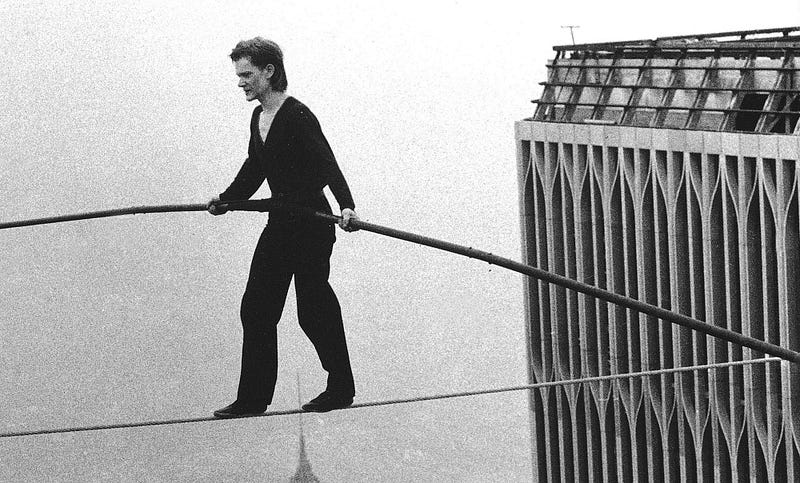

Where are those who take enormous personal risks to take a stand or do a job?

Heroism matters.

Heroism takes many forms. But I just want to be clear, heroism is never the act of being unafraid. If you are unafraid and do something incredibly risky you are either uninformed or just dumb. Heroism is doing that risky thing despite being terrified.

____________

"Most people admired Koufax for putting his religion before his job. I’m sure there were others who were furious, saying that he wasn’t that religious -- and I don’t think he really was -- but that didn’t make any difference. It was his decision and everyone respected it. They understood."

- Longtime Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully

- Longtime Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully

____________

Yuri Gargarin was afraid. John Glenn was afraid. I’m damn sure John Kennedy was afraid when his PT boat was cut in half. I sure know I was afraid many nights when I was a cop in New York. John Lewis was afraid when he stood in front of protesters and faced police clubs and dogs. Curt Flood had to be afraid as he tossed away the only career he knew.

_________________

“For the record, Flood gave up the $100,000 the Phillies would have paid him for the 1970 season to challenge the reserve clause. How many of those who vilified Curt Flood would have given up their jobs to fight for a principle? Not many.”

__________________

And this model is important.

Kids need to know that risk is ok. That high risk is ok. That fear is ok. That overcoming fear is, dare we say? Noble.

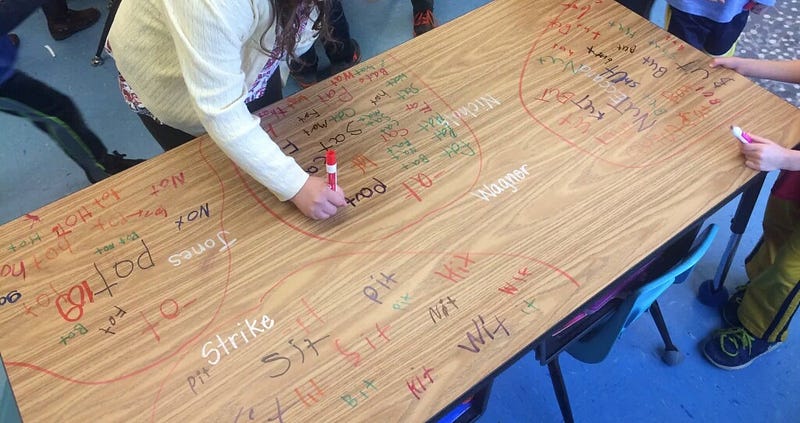

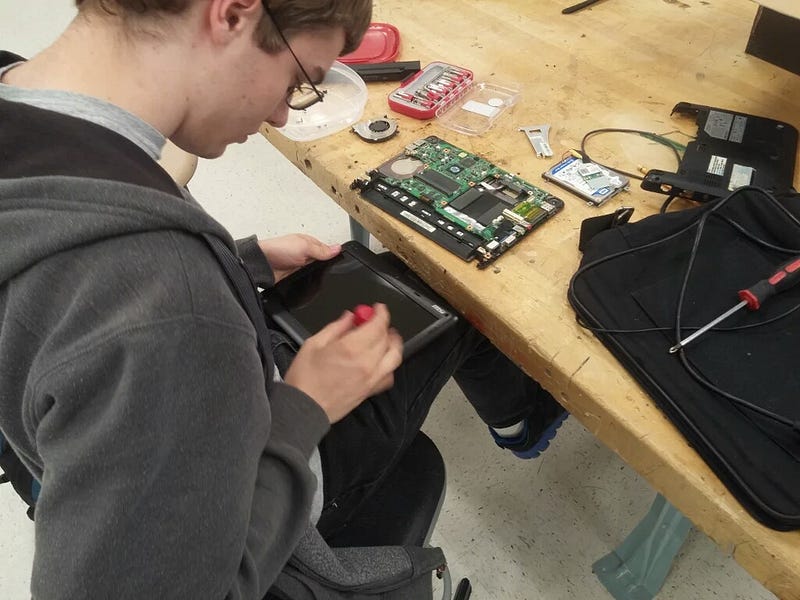

And if this is important, how do we bring this to our students?

The Hero Model

Is the hero model still possible? I think it may be but we need to build it carefully. We have children in our schools whose parents, uncles, aunts, siblings, cousins may be in heroic professions — combat military, police officers, firefighters, emergency medical services — and that’s great but it should never be our job to raise one family’s choices over another’s when talking to kids.

We of course have those same people — not directly related — within our communities and we can ask them to be present and to talk — in age appropriate ways — about risk and fear and responsibility.

And we have history. How do we talk about historical heroes in ways both real and yet effective. I’m not talking about ancient history, like the heroes of my youth necessarily, though they’re included, but any heroes. And maybe that begins with how do we find heroes…

____________________

“Not all acts of heroism need to have a global effect to be defined as brave or courageous. There are many people who, in a variety of ways, have taken up causes in their daily lives. Their efforts show how simply getting involved can open doors to bigger projects involving human rights or rescue opportunities.” — Teaching Tolerance

____________________

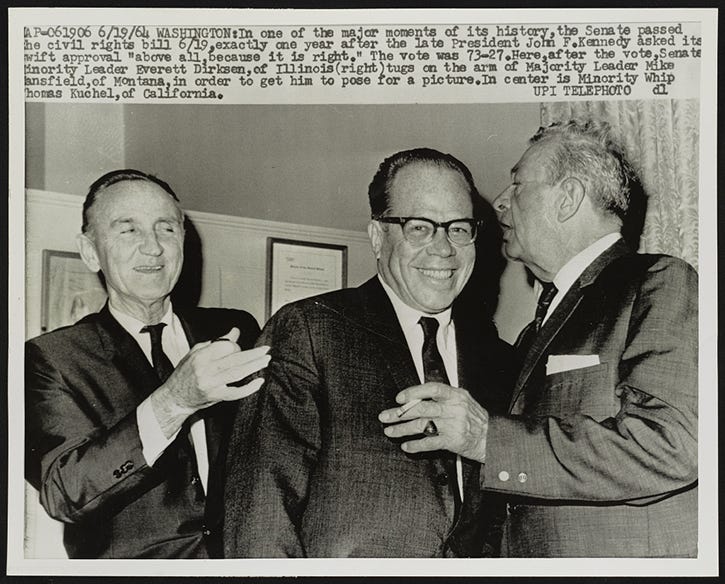

A few years ago I worked with some high school students on John Kennedy’s book Profiles in Courage. It’s a hard book to read now, with not just an academic writing style but a curiously mid-century moral neutrality as to purpose. And yet, it got the kids thinking about political courage. Who demonstrates it now? I suggested a few unheard-of people to them. I asked them to look at Robert Schuman, a French politician who had already been disgraced because of his decisions, who risked his very fragile post-World War II government to make a radical kind of peace with Germany — a peace that has grown into the European Union, and which turned the blood-soaked continent of Europe into the world’s most peaceful, prosperous, and democratic place. Then I presented Everett Dirksen, a right-wing Republican, war hawk, opponent of the idea of ‘one man/one vote,’ who nevertheless joined liberal mid-1960s Democrats to pass the Civil Rights Acts over the opposition of Southern Democratic Senators.

So, one man who briefly collaborated with the Nazis occupying France but who risked all for a united Europe. Another, who thought big city voters should have less of a vote than rural voters (as Trump Republicans do, the idea has not gone away), but who helped pass the most significant civil rights legislation since the US Civil War. Heroes? How do we decide?

Does one act, like Dirksen, make a hero? Do a few flaws, whether Schuman or Mickey Mantle or John Kennedy, deny hero status?

I think about two recent “heros” from my own home town. Mariano Rivera, Yankee relief pitcher and a transplant, employed people, supports kids, built a church. Ray Rice, now disgraced Ravens running back and a born native, worked tirelessly with kids and generously supported the schools. How do we help kids distinguish?

If we want our kids to have heros we must reclaim the heroic narrative. We need to stop focusing, especially with our younger kids, on the historic figures of a disconnected past, and start looking at heroic action and heroic lives in the world our children know.

John Glenn is a hero to my generation because he risked his life not just for his nation but for a belief in science, a belief in wonder, and, we discovered later, for a deep love of his wife, of his community, of his nation and its most vulnerable citizens. He lived a model life through a series of historic moments.

Who is out there today being that kind of person? Let us find them, celebrate them, and abandon our willingness to accept much less in our leadership.

“We tend to think of heroes as being those who are well known, but America is made up of a whole nation of heroes who face problems that are very difficult, and their courage remains largely unsung. Millions of individuals are heroes in their own right.” — John Glenn

- Ira Socol